The Code is the Cartel

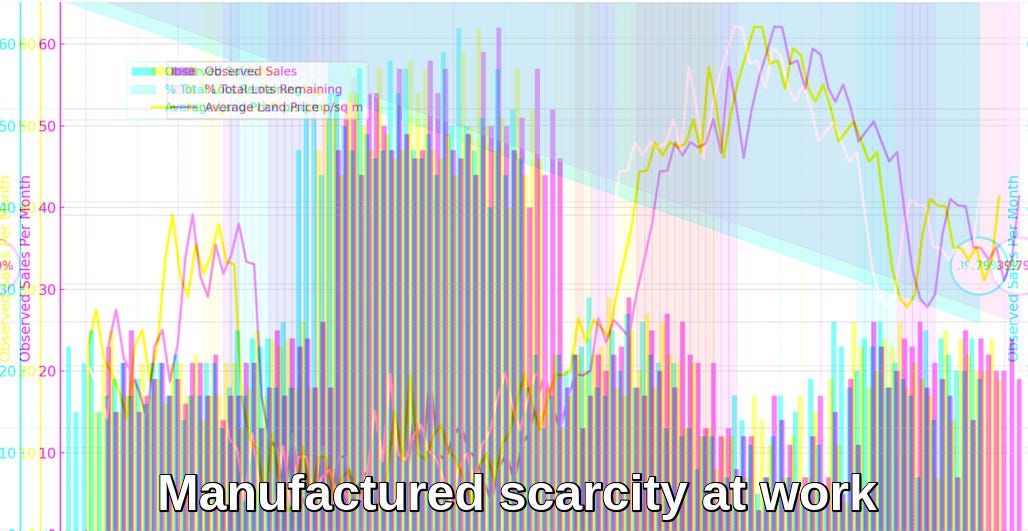

How software turned scarcity into strategy, and neighborhoods into numbers.

Your rent was not set by a landlord in a back room with a calculator. It was shaped by layers of software that started with Google Maps and ended with a rent-bot.

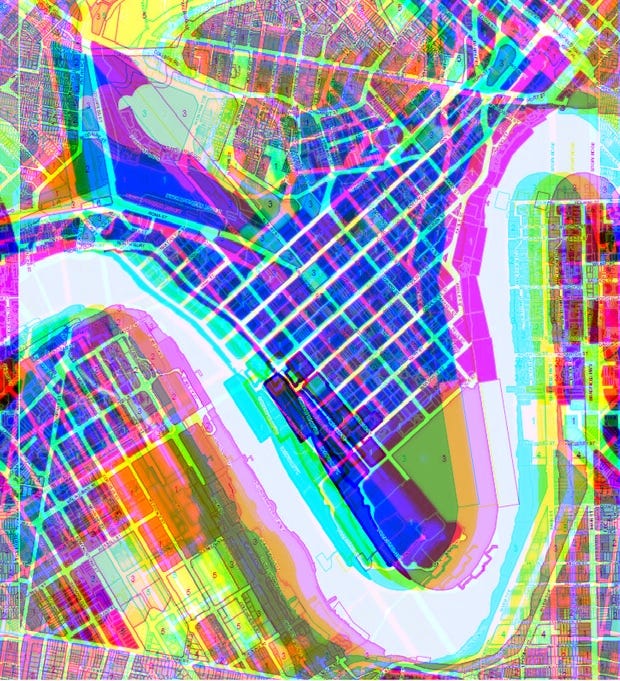

The entry point is deceptively simple. Zoom in on satellite maps, filter for lots over 800 m², cross-check with zoning maps to see where density bonuses apply. The target list is clear: long-held land in the right postcode. The tactic is simple: sign a put/call option. No need to buy the property outright. Control it on paper with minimal cash down.

Once a planning approval looks likely, flip the option, pocketing a windfall in days or weeks. In Queensland, put/call option deeds are common, while sunset clauses have been criticised for allowing contracts to be cancelled then resold at higher prices.

Once proven, these hustles get embedded into software. In the UK, tools like LandInsight and Nimbus Maps allow investors to filter by parcel size, overlay planning rules, and even track “distressed” owners. In Southeast Queensland, Brisbane’s Development.i and the Queensland Globe provide the same raw material, ready for automation.

At the top layer sit the algorithms that make headlines. In the United States, YieldStar (RealPage) and Yardi’s RENTmaximizer recommend rent increases based on pooled, non-public data from multiple landlords. The U.S. Department of Justice and eight states have sued RealPage for facilitating algorithmic collusion, while cities including Seattle, Minneapolis, and Berkeley have banned them outright. The White House Council of Economic Advisers estimates these tools cost renters on average $70 a month—$3.8 billion in total in 2023 alone.

The human consequences are visible. In Ballarat, frontline services launched the Ballarat Zero initiative to end rough sleeping. A pensioner in Brisbane out-negotiated by an option deed. A London renter paying a premium because of algorithmic pricing. A Los Angeles tenant watching every landlord’s rent quote move in lockstep. Each step in the stack looks normal in isolation: a mapping tool, a contract, a pricing engine. Stitched together, they form a machine that eats neighborhoods. Scarcity is manufactured, homes are treated as data points, and housing supply is only important when a mates’ land can be rezoned. Queue ignorance for vacant land, vacant commercial sites, vacant Airbnbs.

When the remnant supply is squeezed and rent-bots steer prices, homelessness becomes predictable, not incidental.

But it doesn’t have to remain dystopian. Technology can be used for justice, like Luyten 3D’s 3D-printed homes for remote and Indigenous communities, or the Ilpeye Ilpeye initiative in Central Australia, where a community used new tech to pioneer its own housing. Or civic data platforms like Urban Intelligence’s PlaceMaker, which councils use to evaluate sites for social and affordable housing. These tools show the same datasets and automation can rebuild communities, not rip them apart.

Underlying all of this is a human right: the right to belong. Author Kevin Bell reminded us “A house is not just a widget – it is a home for the person.” Safe and secure housing is a basic human right, essential for dignity. Without it, the right to education, to family, to health, to community all erode. Homelessness isn’t just a housing failure, it’s a violation of the right to belong. The “Right to the City” reminds us that urban space should be co-created by citizens, not shaped by algorithms and investors.

Ultimately, planning departments need the same data tools that rent-seeking developers deploy. Too often rezonings are approved without any analytics on how that developer actually stages supply, and how those choices ripple into pricing. In property, “market forces” are treated as neutral, almost natural. But in 2025 what drives prices isn’t an invisible hand, it’s concentrated market power, exercised with AI precision from behind the rezoning curtain.

The code is the cartel, until we reclaim it as code for community. The same data must fuel belonging, not eviction. Let’s flip public data towards ‘algos for all’, defending homes the way rent-bots defend profits.